Wooden Town + Zero Fire Engines = Frenchtown's Great Fire of 1878

- Rick Epstein

- Aug 13, 2021

- 9 min read

“It’s a bad thing to have a fire engine that won’t do what is required of it when most needed,” warned the Independent in 1871. The Frenchtown Press issued similar admonitions.

A fire in May of 1876 was like a dress rehearsal for the big one two years later.

At 10:15 p.m. John L. Slack and George Bunn saw a man come out of Gabriel Slater’s hardware store and hurry away on Bridge Street. Upon investigation, they found the front door unfastened and the third-story Masonic meeting hall on fire. They alerted the citizenry, who brought buckets of water. But the fire had spread up between the tin ceiling and the roof, beyond the throwing range of the bucket wielders.

Borough Clerk Silas S. Wright, who had been president of the short-lived Vigilant Fire Company, got the old Vigilant hand-pumper working, and James E. Flagg was soon directing a stream of water into the ceiling to good effect. The fire was extinguished, although the big meeting room was badly damaged. The newspapers’ criticism of the Vigilant seemed undeserved.

It was determined that the store’s own resources had been turned against it. A watering can had been filled with kerosene downstairs for use as an accelerant, causing some to speculate that the incendiary was familiar with the store.

* * *

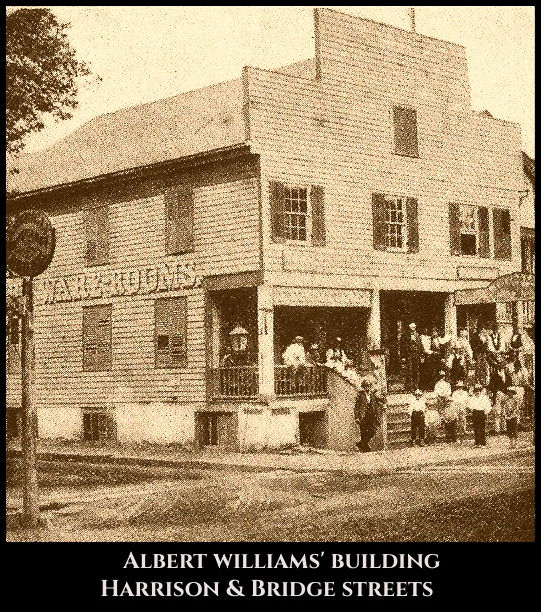

As catastrophe approached, Frenchtown was thrumming. In March of 1878 druggist Albert P. “Bert” Williams bought Isaac Wilgus’ building on the eastern corner of Harrison and Bridge streets at a sheriff’s sale for $4,896. Wilgus moved to Easton, Pa., and became a grocer.

That same month, Levi Able added a barbershop to his eatery, and William Srope moved his legal office into Williams’ newly acquired building. In May the Independent reported that the interior of the American House hotel was being painted and papered and that A.A. Schofield had just opened a photographic studio in Williams’ building.

All these folks would soon be checking their insurance policies or wishing they had one.

* * *

“At a quarter before 1 o’clock on the morning of Saturday, June 29, 1878, while our inhabitants reposed in slumber, the cry of ‘Fire!’ was heard. Two hours thereafter nineteen places of business, six dwelling houses and twenty-one business firms were entirely burned out. The business centre was a mass of charred ruins. Thousands of dollars of valuable machinery was reduced to nothing. The sad havoc which the Press had so often predicted, was completed. Thanks be to God no lives were destroyed. Fortunes were swept away, but life and limb were spared.” – the Press

The fire broke out in the barn of Emanuel K. Deemy, a physician and surgeon raising a family and practicing medicine in a rented house at 41 Bridge Street.

“Be it said to the credit of the ladies, they were the first to see the fire, and the first to make the alarm. Mrs. Charles A. Slack (Sarah) and Mrs. Emley Hyde (Thisby) both saw it at about the same time and gave the alarm. Mrs. Hyde by ringing the dinner bell thro’ Temperance House and in the street. Mrs. A.P. Williams (Mary), who was staying with her sick mother on Bridge street, immediately ran up to her home on Fourth street shouting ‘Fire!’ all the way up Harrison street,” wrote the Independent.

Deemy’s barn contained carriages, his horse, his cow, a son’s two white rabbits, and Levi Able’s horse. Two more barns were adjacent – Thomas Able’s and the bank’s, which contained a horse. Running out in his nightshirt, Deemy managed to rescue his cow, and the banker saved his own horse. But the two other horses and the rabbits perished.

The Vigilant pumper was run out, but “the old dilapidated hand engine refused to throw a pint of water and was abandoned,” the Press noted bitterly.

At 1 a.m. telegrapher Wilbur Slack sent a message to Lambertville that a fire engine was needed. At 1:14 Mayor Adam Haring added: “Send us an engine quick.” A pumper was mounted on a flatcar, and the intervening 16 miles were covered in 19 minutes. It arrived here at 2:36 – in time to help confine the fire to buildings already burning.

The mayor had really put some oomph into his telegraph message to Phillipsburg: “Send engine, quick; whole town on fire.” But the message was not delivered properly and an hour was lost.

On a windless night, a fire goes in any direction that offers fuel.

It spread west from the barns into the abundant wood of the wheel, hub and spoke works of Hann & Williams. James Hann (1834-1922) and Edwin G. Williams (1842-1928) owned the property and employed 15 to 25 men. They had a lot of stock on hand, some of it ready for shipment, so their losses were maximized. The factory was on Harrison Street, with its office in the former LaRoche house on the southeast corner of Second and Harrison. Miss Maggie A. Voorhees’ private school was upstairs.

From there, the fire spread east, west and south. To the east on Second Street was the Union National Bank, which was also the home of banker William S. and Mary Stover and their children. Stover tended to his horse, family and personal goods, while bank president Philip G. Reading and teller Abel B. Haring were packing important papers in wooden boxes and taking them to safety. They toiled until fire and smoke drove them out. The money remained in a large safe, advertised as fireproof, and soon to be tested. Wilbur Slack’s home on Second Street caught fire, and the roof was badly burned before it was extinguished.

Dr. Asher Reiley’s barn would have led the fire eastward to Race Street, but men doused it with water, and that part of downtown was saved.

The fire went west, jumping Harrison Street to burn down the house on the corner of Lower Second Street. It belonged to retiree Samuel Pittenger (1798-1889) and wife Amy (1819-1901). The uninsured Pittenger house collapsed into the street just behind, and barely missing, Charles B. Salter who was passing by.

Other houses along the northern edge of the fire were kept wet and suffered no more than blistered paint. They belonged to Charles Kline, Reuben Hillpot, Dr. Frank T. Eggert and Charles A. Slack. Other homes that were threatened by the fire, but suffered little damage were those of Aaron P. Kachline, William Alpaugh, William Smith, Thomas Able and W.H. Slater.

On the west side of Harrison Street, the fire burned toward Bridge Street, igniting (in order) the American Temperance House’s stables; the building that housed the Press newspaper and print shop upstairs and Kachline & Bro.’s meat shop downstairs; and the American hotel itself.

The Press reported, “The hotel was full and (Emley Hyde) and his lady had just succeeded in working it up to a paying condition by dint of hard work, when the fire fiend enters upon his work of destruction. The dinner bell aroused the guests.”

Charles Salter and his father, Abner, rushed in to save some of the hotel furniture, not pausing to admire the new paint and wallpaper. Trying to exit, George found the back door blocked, so he ran through the burning hotel followed by a sheet of flame. At least that’s how he remembered it 64 years later. Despite the efforts of the Salters and others, “almost the entire contents of the hotel were burned,” wrote the Press.

Spreading south on the eastern side of Harrison, the fire attacked the conjoined holdings of landlord Bert Williams, starting with Frank C. Miller’s jewelry store and John McIntyre’s harness shop and a manufacturer of bed bottoms upstairs; then William Smith’s shoe shop and Joseph Hawk’s meat store, with George Hummer’s cabinetry shop upstairs; then Srope’s new legal office; and then the building on the corner that housed Hummer’s furniture store and undertaking establishment. Upstairs, the front room was Miss Mattie Hummer’s dressmaking shop.

McIntyre was out of town, says the Independent, and lost his stored household goods, harness-making equipment, three sets of harness, all his clothing, $11 in silver, and his Union Army discharge papers. The newspaper awarded him the unenviable distinction of being “the nearest burned out of everything than every other man who was touched by the fire.”

Williams' drug store was in the east part of his building. Two display cases, a soda fountain, prescription files, and two chandeliers were hauled out to safety. Then, with the inferno approaching, two young men, T. Powers Williams and Sam Stahler, met Bert Williams in front of his store. Powers remembered, “Bert unlocked the store and invited Sam and me in. He went to the closet where he kept liquors for medicinal purposes only, pulled out a demijohn and, having procured a glass, gave Sam and me each a big hooker. He put the demijohn back in the closet and turned the key. Sam and I thought it was a shame as we could so easily rescue the demijohn, but Bert thought differently. We went out of the store and Bert locked the door. We were the last three persons to leave the building, for in less than a half hour it was wrapped in flames.” A “big hooker” probably meant something different then.

Besides the liquor and a complete stock of drugs, Bert Williams also left behind $29 belonging to the Frenchtown Cornet Band. He was the ensemble’s treasurer (and tuba player).

Upstairs from the drug store was Schofield’s new photo studio. He managed to remove most of his equipment and materials in time, but left behind $17 in silver and cameras belonging to the Kachline brothers and landlord Williams.

Raging east on Bridge Street, the fire burned Levi Able’s building, whose first story was brick, and top two levels were frame. It housed his barbershop/ restaurant/bakery on the ground floor. He lived upstairs with wife Kate and children Edwin, 5, and Phebe, 1.

Only a 12-foot gap separated Able’s unlikely lash-up of uses from the house that the Deemys were renting. When Able’s building was ready to collapse, men pushed on the east wall so it the fiery wreckage would fall away from the Deemy house. Stone construction and the timely arrival of the Lambertville firefighters combined to save the Deemy house, thereby protecting the wooden buildings farther east. Even so, all the wood on the west wall of the house had turned to charcoal and $200 worth of repairs would be needed.

Meanwhile on the western front, the fire spread from the hotel, consuming a row of four buildings that were, in order, Miss Lydia Stryker’s millinery shop; the home of carriage-maker James Osmun, wife Josephine and teenage son John C.; Mrs. Frances Stryker’s residence; and the home of merchant Daniel F. Moore, wife Phoebe, and children Ella, William, Stella, Mary and Edwin, ranging in age from 8 to 18.

The fire tried to jump the alley to Hugh Warford’s three-story brick residence, but carpets in the house were cut into strips and draped over the wooden cornices on the hot side of the house. Men with ladders, ropes and buckets worked in the blistering heat to keep the carpet well-soaked.

Although his residence was saved, Warford was the biggest loser that day. He owned all the buildings starting with the hotel’s stables going south on Harrison and around the Bridge Street corner and down to and including his residence – except for the Osmun home in the row of four, which was owned by Levi Able. Insurance covered about half his losses.

On the southern side of Bridge Street “...at Loux & Bunn’s tin shop, H.H. Pittenger’s store and dwelling, and Ishmael Brink’s store and dwelling, it was very hard and hot work to prevent those buildings from drawing the fire across the street. But brave men worked with a will and fought it as though they were working to save their very lives instead of their property. Mr. Wm. Gordon Jr., worked on the portico roof of H.H. Pittenger’s residence, throwing water on the front of that building until the danger was over, when he fell back through the window into the house exhausted. In the fall he injured his shoulder and has been compelled to carry his arm in a sling since,” wrote the Independent.

The spread of the fire was also impeded by all of the street-side trees that were tall and in full leaf, providing a buffer.

“Nearly every household in the vicinity of the fire was turned inside out, and the streets were lined with articles of housekeeping of every description until late in the forenoon, but of the many articles that were set without a watch over them, we have heard of no thefts,” the Independent reported.

With their furniture store in flames, George and Mary Hummer tried to rescue what they could from their endangered Second Street home. Mary handed off her 16-month-old son, Charles, the better to grab up her belongings.

The babysitter disappeared in the chaos, and when she was found, she couldn't remember what she'd done with Charles. The boy was of an age to ambulate, so he might have toddled off into the smoky gloom. That's assuming this family legend is factual.

Clarence Fargo noted in “History of Frenchtown” that some of the items were carried to the other side of the creek, and the front lawn of 12 Bridge Street “was filled with household goods and personal effects of every description.” Levi Able’s barber chair was saved, which must have been small consolation; he’d lost two buildings, with insurance covering only half his losses.

The Independent wrote, “To illustrate the strength of men under excitement, we will mention that four men carried a piano from H.H. Pittenger’s residence to an alley in the rear, and it required ten men to return it after the excitement had died out.”

Brink’s hardware store caught fire, but his friends put it out and kept the place soaked.

At 3:20 Phillipsburg firefighters telegraphed that their fire engines were ready to come south, but Frenchtown station agent Bryan Hough advised, “Will not need engines. Fire is under control now.”

Mary Quick and husband Stewart resided in the American hotel with 3-month-old son William. He had been on duty in the telegraph office, but was able to run home and help Mary rescue some of their belongings. After the emergency passed, Mary, “overcome by the excitement and overwork, fell in a fainting fit, and after an hour was with difficulty brought to consciousness,” the Independent reported. The family moved into the Railroad House.

Next: The Aftermath

Comments